Introduction to Python#

Before we get started 1…#

most of what you’ll see within this lecture was prepared by Ross Markello, Michael Notter and Peer Herholz and further adapted for this course by Peer Herholz

based on Tal Yarkoni’s “Introduction to Python” lecture at Neurohackademy 2019

based on http://www.stavros.io/tutorials/python/ & http://www.swaroopch.com/notes/python

based on oesteban/biss2016 & jvns/pandas-cookbook

Objectives 📍#

learn basic and efficient usage of the python programming language

what is python & how to utilize it

building blocks of & operations in python

What is Python?#

Python is a programming language

Specifically, it’s a widely used/very flexible, high-level, general-purpose, dynamic programming language

That’s a mouthful! Let’s explore each of these points in more detail…

Widely-used#

Python is the fastest-growing major programming language

Top 3 overall (with JavaScript, Java)

High-level#

Python features a high level of abstraction

Many operations that are explicit in lower-level languages (e.g., C/C++) are implicit in Python

E.g., memory allocation, garbage collection, etc.

Python lets you write code faster

File reading in Java#

import java.io.BufferedReader;

import java.io.FileReader;

import java.io.IOException;

public class ReadFile {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException{

String fileContents = readEntireFile("./foo.txt");

}

private static String readEntireFile(String filename) throws IOException {

FileReader in = new FileReader(filename);

StringBuilder contents = new StringBuilder();

char[] buffer = new char[4096];

int read = 0;

do {

contents.append(buffer, 0, read);

read = in.read(buffer);

} while (read >= 0);

return contents.toString();

}

}

File-reading in Python#

open(filename).read()

General-purpose#

You can do almost everything in Python

Comprehensive standard library

Enormous ecosystem of third-party packages

Widely used in many areas of software development (web, dev-ops, data science, etc.)

Dynamic#

Code is interpreted at run-time

No compilation process*; code is read line-by-line when executed

Eliminates delays between development and execution

The downside: poorer performance compared to compiled languages

(Try typing import antigravity into a new cell and running it!)

What we will do in this section of the course is a short introduction to Python to help beginners to get familiar with this programming language.

It is divided into the following chapters:

Here’s what we will focus on in the first block:

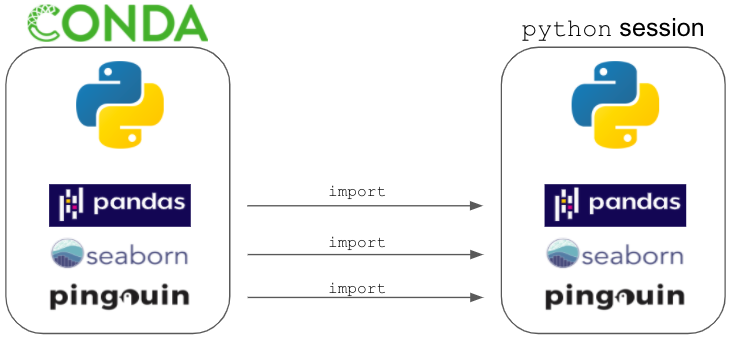

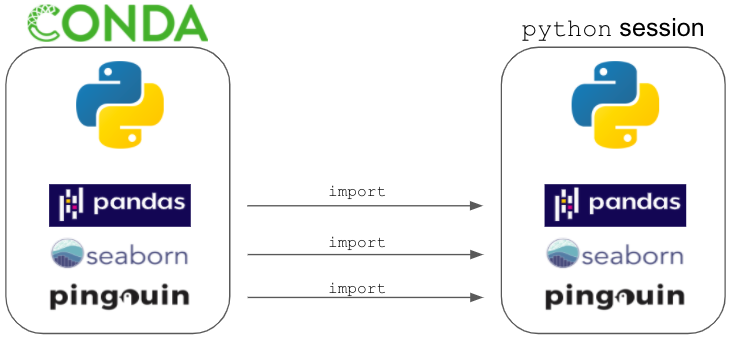

Modules#

Most of the functionality in Python is provided by modules. To use a module in a Python program it first has to be imported. A module can be imported using the import statement.

For example, to import the module math, which contains many standard mathematical functions, we can do:

import math

This includes the whole module and makes it available for use later in the program. For example, we can do:

import math

x = math.cos(2 * math.pi)

print(x)

1.0

Importing the whole module us often times unnecessary and can lead to longer loading time or increase the memory consumption. An alternative to the previous method, we can also choose to import only a few selected functions from a module by explicitly listing which ones we want to import:

from math import cos, pi

x = cos(2 * pi)

print(x)

1.0

You can make use of tab again to get a list of functions/classes/etc. for a given module. Try it out via navigating the cursor behind the import statement and press tab:

from math import

Comparably you can also use the help function to find out more about a given module:

import math

help(math)

Help on module math:

NAME

math

MODULE REFERENCE

https://docs.python.org/3.10/library/math.html

The following documentation is automatically generated from the Python

source files. It may be incomplete, incorrect or include features that

are considered implementation detail and may vary between Python

implementations. When in doubt, consult the module reference at the

location listed above.

DESCRIPTION

This module provides access to the mathematical functions

defined by the C standard.

FUNCTIONS

acos(x, /)

Return the arc cosine (measured in radians) of x.

The result is between 0 and pi.

acosh(x, /)

Return the inverse hyperbolic cosine of x.

asin(x, /)

Return the arc sine (measured in radians) of x.

The result is between -pi/2 and pi/2.

asinh(x, /)

Return the inverse hyperbolic sine of x.

atan(x, /)

Return the arc tangent (measured in radians) of x.

The result is between -pi/2 and pi/2.

atan2(y, x, /)

Return the arc tangent (measured in radians) of y/x.

Unlike atan(y/x), the signs of both x and y are considered.

atanh(x, /)

Return the inverse hyperbolic tangent of x.

ceil(x, /)

Return the ceiling of x as an Integral.

This is the smallest integer >= x.

comb(n, k, /)

Number of ways to choose k items from n items without repetition and without order.

Evaluates to n! / (k! * (n - k)!) when k <= n and evaluates

to zero when k > n.

Also called the binomial coefficient because it is equivalent

to the coefficient of k-th term in polynomial expansion of the

expression (1 + x)**n.

Raises TypeError if either of the arguments are not integers.

Raises ValueError if either of the arguments are negative.

copysign(x, y, /)

Return a float with the magnitude (absolute value) of x but the sign of y.

On platforms that support signed zeros, copysign(1.0, -0.0)

returns -1.0.

cos(x, /)

Return the cosine of x (measured in radians).

cosh(x, /)

Return the hyperbolic cosine of x.

degrees(x, /)

Convert angle x from radians to degrees.

dist(p, q, /)

Return the Euclidean distance between two points p and q.

The points should be specified as sequences (or iterables) of

coordinates. Both inputs must have the same dimension.

Roughly equivalent to:

sqrt(sum((px - qx) ** 2.0 for px, qx in zip(p, q)))

erf(x, /)

Error function at x.

erfc(x, /)

Complementary error function at x.

exp(x, /)

Return e raised to the power of x.

expm1(x, /)

Return exp(x)-1.

This function avoids the loss of precision involved in the direct evaluation of exp(x)-1 for small x.

fabs(x, /)

Return the absolute value of the float x.

factorial(x, /)

Find x!.

Raise a ValueError if x is negative or non-integral.

floor(x, /)

Return the floor of x as an Integral.

This is the largest integer <= x.

fmod(x, y, /)

Return fmod(x, y), according to platform C.

x % y may differ.

frexp(x, /)

Return the mantissa and exponent of x, as pair (m, e).

m is a float and e is an int, such that x = m * 2.**e.

If x is 0, m and e are both 0. Else 0.5 <= abs(m) < 1.0.

fsum(seq, /)

Return an accurate floating point sum of values in the iterable seq.

Assumes IEEE-754 floating point arithmetic.

gamma(x, /)

Gamma function at x.

gcd(*integers)

Greatest Common Divisor.

hypot(...)

hypot(*coordinates) -> value

Multidimensional Euclidean distance from the origin to a point.

Roughly equivalent to:

sqrt(sum(x**2 for x in coordinates))

For a two dimensional point (x, y), gives the hypotenuse

using the Pythagorean theorem: sqrt(x*x + y*y).

For example, the hypotenuse of a 3/4/5 right triangle is:

>>> hypot(3.0, 4.0)

5.0

isclose(a, b, *, rel_tol=1e-09, abs_tol=0.0)

Determine whether two floating point numbers are close in value.

rel_tol

maximum difference for being considered "close", relative to the

magnitude of the input values

abs_tol

maximum difference for being considered "close", regardless of the

magnitude of the input values

Return True if a is close in value to b, and False otherwise.

For the values to be considered close, the difference between them

must be smaller than at least one of the tolerances.

-inf, inf and NaN behave similarly to the IEEE 754 Standard. That

is, NaN is not close to anything, even itself. inf and -inf are

only close to themselves.

isfinite(x, /)

Return True if x is neither an infinity nor a NaN, and False otherwise.

isinf(x, /)

Return True if x is a positive or negative infinity, and False otherwise.

isnan(x, /)

Return True if x is a NaN (not a number), and False otherwise.

isqrt(n, /)

Return the integer part of the square root of the input.

lcm(*integers)

Least Common Multiple.

ldexp(x, i, /)

Return x * (2**i).

This is essentially the inverse of frexp().

lgamma(x, /)

Natural logarithm of absolute value of Gamma function at x.

log(...)

log(x, [base=math.e])

Return the logarithm of x to the given base.

If the base not specified, returns the natural logarithm (base e) of x.

log10(x, /)

Return the base 10 logarithm of x.

log1p(x, /)

Return the natural logarithm of 1+x (base e).

The result is computed in a way which is accurate for x near zero.

log2(x, /)

Return the base 2 logarithm of x.

modf(x, /)

Return the fractional and integer parts of x.

Both results carry the sign of x and are floats.

nextafter(x, y, /)

Return the next floating-point value after x towards y.

perm(n, k=None, /)

Number of ways to choose k items from n items without repetition and with order.

Evaluates to n! / (n - k)! when k <= n and evaluates

to zero when k > n.

If k is not specified or is None, then k defaults to n

and the function returns n!.

Raises TypeError if either of the arguments are not integers.

Raises ValueError if either of the arguments are negative.

pow(x, y, /)

Return x**y (x to the power of y).

prod(iterable, /, *, start=1)

Calculate the product of all the elements in the input iterable.

The default start value for the product is 1.

When the iterable is empty, return the start value. This function is

intended specifically for use with numeric values and may reject

non-numeric types.

radians(x, /)

Convert angle x from degrees to radians.

remainder(x, y, /)

Difference between x and the closest integer multiple of y.

Return x - n*y where n*y is the closest integer multiple of y.

In the case where x is exactly halfway between two multiples of

y, the nearest even value of n is used. The result is always exact.

sin(x, /)

Return the sine of x (measured in radians).

sinh(x, /)

Return the hyperbolic sine of x.

sqrt(x, /)

Return the square root of x.

tan(x, /)

Return the tangent of x (measured in radians).

tanh(x, /)

Return the hyperbolic tangent of x.

trunc(x, /)

Truncates the Real x to the nearest Integral toward 0.

Uses the __trunc__ magic method.

ulp(x, /)

Return the value of the least significant bit of the float x.

DATA

e = 2.718281828459045

inf = inf

nan = nan

pi = 3.141592653589793

tau = 6.283185307179586

FILE

/Users/peerherholz/anaconda3/envs/nowaschool/lib/python3.10/lib-dynload/math.cpython-310-darwin.so

It is also possible to give an imported module or symbol your own access name with the as additional:

import numpy as np

from math import pi as number_pi

x = np.rad2deg(number_pi)

print(x)

180.0

You can basically provide any name (given it’s following python/coding conventions) but focusing on intelligibility won’t be the worst idea:

import matplotlib as pineapple

pineapple.

Exercise 1.1#

Import the max from numpy and find out what it does.

# write your solution in this code cell

from numpy import max

help(max)

Exercise 1.2#

Import the scipy package and assign the access name middle_earth and check its functions.

# write your solution in this code cell

import scipy as middle_earth

help(middle_earth)

Exercise 1.3#

What happens when we try to import a module that is either misspelled or doesn’t exist in our environment or at all?

pythonprovides us a hint that themodulename might be misspelledwe’ll get an

errortelling us that themoduledoesn’t existpythonautomatically searches for themoduleand if it exists downloads/installs it

import welovethisschool

Namespaces and imports#

Python is very serious about maintaining orderly

namespacesIf you want to use some code outside the current scope, you need to explicitly “

import” itPython’s import system often annoys beginners, but it substantially increases

codeclarityAlmost completely eliminates naming conflicts and confusion

Help and Descriptions#

Using the function help we can get a description of almost all functions.

help(math.log)

Help on built-in function log in module math:

log(...)

log(x, [base=math.e])

Return the logarithm of x to the given base.

If the base not specified, returns the natural logarithm (base e) of x.

math.log(10)

2.302585092994046

math.log(10, 2)

3.3219280948873626

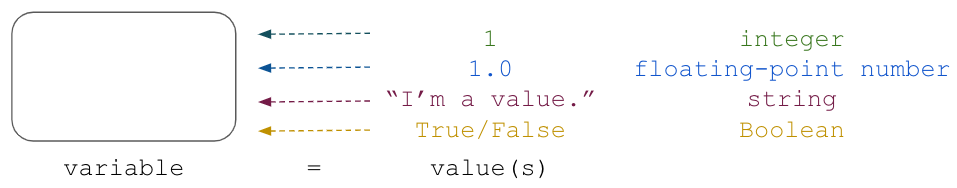

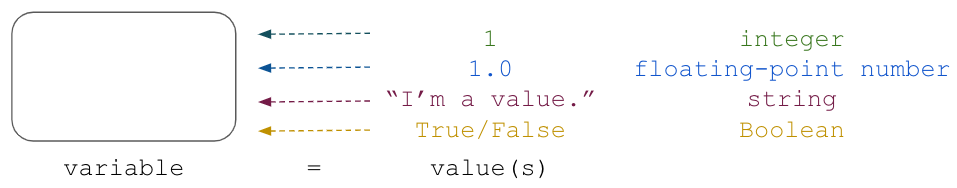

Variables and data types#

in programming

variablesare things that storevaluesin

Python, we declare avariableby assigning it avaluewith the=signname = valuecode

variables!= math variablesin mathematics

=refers to equality (statement of truth), e.g.y = 10x + 2in coding

=refers to assignments, e.g.x = x + 1

Variables are pointers, not data stores!

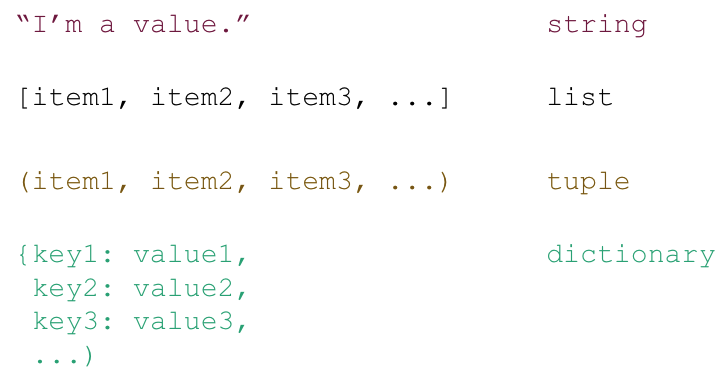

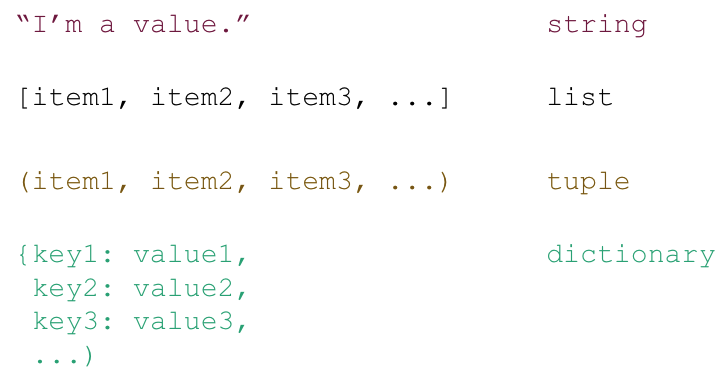

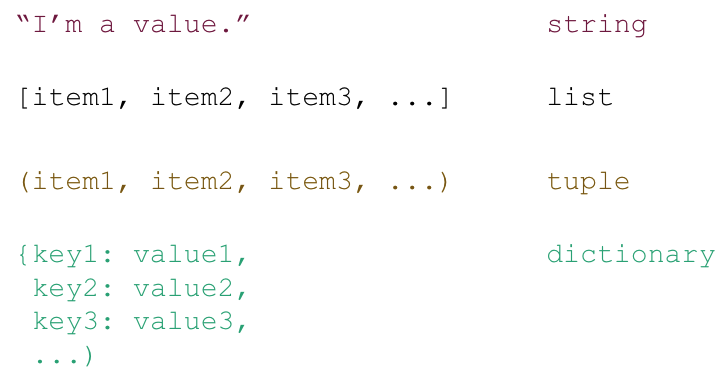

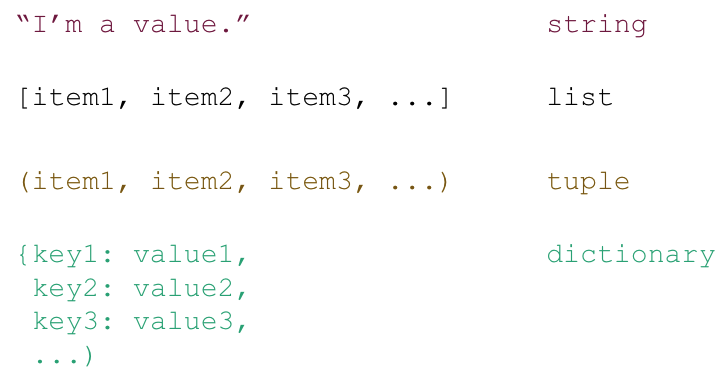

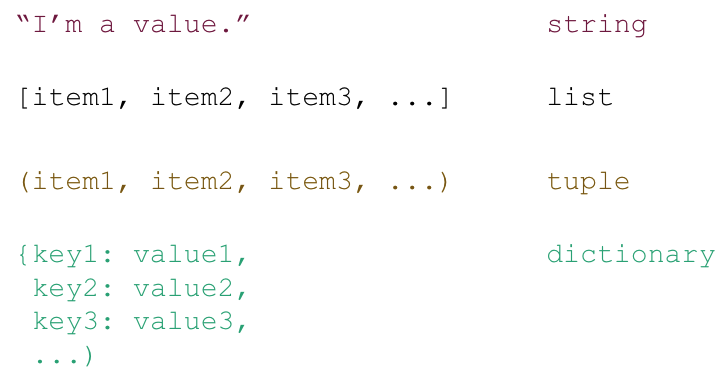

Pythonsupports a variety ofdata typesandstructures:booleansnumbers(ints,floats, etc.)stringslistsdictionariesmany others!

We don’t specify a variable’s type at assignment

Symbol names#

Variable names in Python can contain alphanumerical characters a-z, A-Z, 0-9 and some special characters such as _. Normal variable names must start with a letter.

By convention, variable names start with a lower-case letter, and Class names start with a capital letter.

In addition, there are a number of Python keywords that cannot be used as variable names. These keywords are:

and, as, assert, break, class, continue, def, del, elif, else, except, exec, finally, for, from, global, if, import, in, is, lambda, not, or, pass, print, raise, return, try, while, with, yield

Assignment#

(Not an homework assignment but the operator in python.)

The assignment operator in Python is =. Python is a dynamically typed language, so we do not need to specify the type of a variable when we create one.

Assigning a value to a new variable creates the variable:

x = 1.0

Again, this does not mean that x equals 1 but that the variable x has the value 1. Thus, our variable x is stored in the respective namespace:

x

1.0

This means that we can directly utilize the value of our variable:

x + 3

4.0

Although not explicitly specified, a variable does have a type associated with it. The type is derived from the value it was assigned.

type(x)

float

If we assign a new value to a variable, its type can change.

x = 1

type(x)

int

This outline one further very important characteristic of python (and many other programming languages): variables can be directly overwritten by assigning them a new value. We don’t get an error like “This namespace is already taken.” Thus, always remember/keep track of what namespaces were already used to avoid unintentional deletions/errors (reproducibility/replicability much?).

ring_bearer = 'Bilbo'

ring_bearer

'Bilbo'

ring_bearer = 'Frodo'

ring_bearer

'Frodo'

If we try to use a variable that has not yet been defined we get an NameError (Note for later sessions, that we will use in the notebooks try/except blocks to handle the exception, so the notebook doesn’t stop. The code below will try to execute print function and if the NameError occurs the error message will be printed. Otherwise, an error will be raised. You will learn more about exception handling later.):

try:

print(Peer)

except(NameError) as err:

print("NameError", err)

else:

raise

NameError name 'Peer' is not defined

Variable names:

Can include

letters(A-Z),digits(0-9), andunderscores( _ )Cannot start with a

digitAre case sensitive (questions: where did “lower/upper case” originate?)

This means that, for example:

shire0is a valid variable name, whereas0shireis notshireandShireare different variables

Exercise 2.1#

Create the following variables n_elves, n_dwarfs, n_humans with the respective values 3, 7.0 and nine.

# write your solution here

n_elves = 3

n_dwarfs = 7.0

n_humans = "nine"

Exercise 2.2#

What’s the output of n_elves + n_dwarfs?

n_elves + n_dwarfs10

10.0

n_elves + n_dwarfs

Exercise 2.3#

Consider the following lines of code.

ring_bearer = 'Gollum'

ring_bearer

ring_bearer = 'Bilbo'

ring_bearer

What is the final output?

'Bilbo''Gollum'neither, the variable got deleted

ring_bearer = 'Gollum'

ring_bearer

ring_bearer = 'Bilbo'

ring_bearer

Fundamental types & data structures#

Most code requires more complex structures built out of basic data

typesdata typerefers to thevaluethat isassignedto avariablePythonprovides built-in support for many common structuresMany additional structures can be found in the collections module

Most of the time you’ll encounter the following data types

integers(e.g.1,42,180)floating-point numbers(e.g.1.0,42.42,180.90)strings(e.g."Rivendell","Weathertop")Boolean(True,False)

If you’re unsure about the data type of a given variable, you can always use the type() command.

Integers#

Lets check out the different data types in more detail, starting with integers. Intergers are natural numbers that can be signed (e.g. 1, 42, 180, -1, -42, -180).

x = 1

type(x)

int

n_nazgul = 9

type(n_nazgul)

int

remaining_rings = -1

type(remaining_rings)

int

Floating-point numbers#

So what’s the difference to floating-point numbers? Floating-point numbers are decimal-point number that can be signed (e.g. 1.0, 42.42, 180.90, -1.0, -42.42, -180.90).

x_float = 1.0

type(x_float)

float

n_nazgul_float = 9.0

type(n_nazgul_float)

float

remaining_rings_float = -1.0

type(remaining_rings_float)

float

Strings#

Next up: strings. Strings are basically text elements, from letters to words to sentences all can be/are strings in python. In order to define a string, Python needs quotation marks, more precisely strings start and end with quotation marks, e.g. "Rivendell". You can choose between " and ' as both will work (NB: python will put ' around strings even if you specified "). However, it is recommended to decide on one and be consistent.

location = "Weathertop"

type(location)

str

abbreviation = 'LOTR'

type(abbreviation)

str

book_one = "The fellowship of the ring"

type(book_one)

str

Booleans#

How about some Booleans? At this point it gets a bit more “abstract”. While there are many possible numbers and strings, a Boolean can only have one of two values: True or False. That is, a Boolean says something about whether something is the case or not. It’s easier to understand with some examples. First try the type() function with a Boolean as an argument.

b1 = True

type(b1)

bool

b2 = False

type(b2)

bool

lotr_is_awesome = True

type(lotr_is_awesome)

bool

Interestingly, True and False also have numeric values! True has a value of 1 and False has a value of 0.

True + True

2

False + False

0

Converting data types#

As mentioned before the data type is not set when assigning a value to a variable but determined based on its properties. Additionally, the data type of a given value can also be changed via set of functions.

int()-> convert thevalueof avariableto anintegerfloat()-> convert thevalueof avariableto afloating-point numberstr()-> convert thevalueof avariableto astringbool()-> convert thevalueof avariableto aBoolean

int("4")

4

float(3)

3.0

str(2)

'2'

bool(1)

True

Exercise 3.1#

Define the following variables with the respective values and data types: fellowship_n_humans with a value of two as a float, fellowship_n_hobbits with a value of four as a string and fellowship_n_elves with a value of one as an integer.

# write your solution here

fellowship_n_humans = 2.0

fellowship_n_hobbits = 'four'

fellowship_n_elves = 1

Exercise 3.2#

What outcome would you expect based on the following lines of code?

True - Falsetype(True)

1bool

Exercise 3.3#

Define two variables, fellowship_n_dwarfs with a value of one as a string and fellowship_n_wizards with a value of one as a float. Subsequently, change the data type of fellowship_n_dwarfs to integer and the data type of fellowship_n_wizard to string.

fellowship_n_dwarfs = 1.0

fellowship_n_wizards = '1.0'

int(fellowship_n_dwarfs)

str(fellowship_n_wizards)

Why do programming/science in Python?#

Lets go through some advantages of the python programming language.

Easy to learn#

Readable, explicit syntax

Most packages are very well documented

e.g.,

scikit-learn’s documentation is widely held up as a model

A huge number of tutorials, guides, and other educational materials

Comprehensive standard library#

The Python standard library contains a huge number of high-quality modules

When in doubt, check the standard library first before you write your own tools!

For example:

os: operating system toolsre: regular expressionscollections: useful data structuresmultiprocessing: simple parallelization toolspickle: serializationjson: reading and writing JSON

Exceptional external libraries#

Pythonhas very good (often best-in-class) externalpackagesfor almost everythingParticularly important for “data science”, which draws on a very broad toolkit

Package management is easy (

conda,pip)Examples:

Web development: flask, Django

Database ORMs: SQLAlchemy, Django ORM (w/ adapters for all major DBs)

Scraping/parsing text/markup: beautifulsoup, scrapy

Natural language processing (NLP): nltk, gensim, textblob

Numerical computation and data analysis: numpy, scipy, pandas, xarray, statsmodels, pingouin

Machine learning: scikit-learn, Tensorflow, keras

Image processing: pillow, scikit-image, OpenCV

audio processing: librosa, pyaudio

Plotting: matplotlib, seaborn, altair, ggplot, Bokeh

GUI development: pyQT, wxPython

Testing: py.test

Etc. etc. etc.

(Relatively) good performance#

Pythonis a high-level dynamic language — this comes at a performance costFor many (not all!) use cases, performance is irrelevant most of the time

In general, the less

Pythoncode you write yourself, the better your performance will beMuch of the standard library consists of

Pythoninterfaces toCfunctionsNumpy,scikit-learn, etc. all rely heavily onC/C++orFortran

Python vs. other data science languages#

Pythoncompetes for mind share with many other languagesMost notably,

RTo a lesser extent,

Matlab,Mathematica,SAS,Julia,Java,Scala, etc.

R#

R is dominant in traditional statistics and some fields of science

Has attracted many SAS, SPSS, and Stata users

Exceptional statistics support; hundreds of best-in-class libraries

Designed to make data analysis and visualization as easy as possible

Slow

Language quirks drive many experienced software developers crazy

Less support for most things non-data-related

MATLAB#

A proprietary numerical computing language widely used by engineers

Good performance and very active development, but expensive

Closed ecosystem, relatively few third-party libraries

There is an open-source port (Octave)

Not suitable for use as a general-purpose language

So, why Python?#

Why choose Python over other languages?

Arguably none of these offers the same combination of readability, flexibility, libraries, and performance

Python is sometimes described as “the second best language for everything”

Doesn’t mean you should always use Python

Depends on your needs, community, etc.

You can have your cake and eat it!#

Many languages—particularly R—now interface seamlessly with Python

You can work primarily in Python, fall back on R when you need it (or vice versa)

The best of all possible worlds?

The core Python “data science” stack#

The Python ecosystem contains tens of thousands of packages

Several are very widely used in data science applications:

Jupyter: interactive notebooks

Numpy: numerical computing in Python

pandas: data structures for Python

Scipy: scientific Python tools

Matplotlib: plotting in Python

scikit-learn: machine learning in Python

We’ll cover the first three very briefly here

Other tutorials will go into greater detail on most of the others

The core “Python for psychology/neuroscience” stack#

The

Python ecosystemcontains tens of thousands ofpackagesSeveral are very widely used in psychology research:

Jupyter: interactive notebooks

Numpy: numerical computing in

Pythonpandas: data structures for

PythonScipy: scientific

PythontoolsMatplotlib: plotting in

Pythonseaborn: plotting in

Pythonscikit-learn: machine learning in

Pythonstatsmodels: statistical analyses in

Pythonpingouin: statistical analyses in

Pythonpsychopy: running experiments in

Pythonnilearn: brain imaging analyses in `Python``

mne: electrophysiology analyses in

Python

Execept

scikit-learn,nilearnandmne, we’ll cover all very briefly in this coursethere are many free tutorials online that will go into greater detail and also cover the other

packages

Introduction to Python II#

Here’s what we will focus on in the second block.

Objectives 📍#

learn basic and efficient usage of the python programming language

building blocks of & operations in python

operators&comparisonsstrings,lists,tuples&dictionaries

Recap of the prior section#

Before we dive into new endeavors, it might be important to briefly recap the things we’ve talked about so far. Specifically, we will do this to evaluate if everyone’s roughly on the same page. Thus, if some of the aspects within the recap are either new or fuzzy to you, please have a quick look at the respective part of the last section again and as usual: ask questions wherever something is not clear.

What is Python?#

Python is a programming language

Specifically, it’s a widely used/very flexible, high-level, general-purpose, dynamic programming language

That’s a mouthful! Let’s explore each of these points in more detail…

Module#

Most of the functionality in Python is provided by modules. To use a module in a Python program it first has to be imported. A module can be imported using the import statement.

Assuming you want to import the entire pandas module to do some data exploration, wrangling and statistics, how would you do that?

# Pleae write your solution in this cell

import pandas

As this might be a bit hard to navigate, specifically for finding/referencing functions. Thus, it might be a good idea to provide a respective access name. For example, could you show how you would provide the pandas module the access name pd?

# Please write your solution in this cell

import pandas as pd

During your analyzes you recognize that some of the analyses you want to run require functions from the statistics module pingouin. Is there a way to only import the functions you want from this module, e.g. the wilcoxon test?

# Please write your solution in this cell

from pingouin import wolcoxon

Variables and data types#

in programming

variablesare things that storevaluesin

Python, we declare avariableby assigning it avaluewith the=signname = valuecode

variables!= math variablesin mathematics

=refers to equality (statement of truth), e.g.y = 10x + 2in coding

=refers to assignments, e.g.x = x + 1

Variables are pointers, not data stores!

Pythonsupports a variety ofdata typesandstructures:booleansnumbers(ints,floats, etc.)stringslistsdictionariesmany others!

We don’t specify a variable’s type at assignment

Assignment#

(Not an homework assignment but the operator in python.)

The assignment operator in Python is =. Python is a dynamically typed language, so we do not need to specify the type of a variable when we create one.

Assigning a value to a new variable creates the variable:

Within your analyzes you need to create a variable called n_students and assign it the value 21, how would that work?

# Please write your solution in this cell

n_students = 21

Quickly after you realize that the value should actually be 20. What options do you have to change the value of this variable?

# Please write your solution in this cell

n_students = 20

n_students = n_students - 1

During the analyzes you noticed that the data type of n_students changed. How can you find out the data type?

# Please write your solution in this cell

type(n_students)

Is there a way to change the data type of n_students to something else, e.g. float?

# Please write your solution in this cell

float(n_students)

Along the way you want to create another variable, this time called acquisition_time and the value December. How would we do that and what data type would that be?

import pandas as pd

# Please write your solution here

acquisition_time = "December"

type(acquisition_time)

As a final step you want to create two variables that indicate that the outcome of a statistical test is either significant or not. How would you do that for the following example: for outcome_anova it’s true that the result was significant and for outcome_ancova it’s false that the result was significant?

# Please write your solution in this cell

outcome_anova = True

outcome_ancova = False

Alright, thanks for taking the time to go through this recap. Again: if you could solve/answer all questions, you should have the information/knowledge needed for this session.

Here’s what we will focus on in the first block:

Operators and comparisons#

One of the most basic utilizations of python might be simple arithmetic operations and comparisons. operators and comparisons in python work as one would expect:

Arithmetic operatorsavailable inpython:+,-,*,/,**power,%modulocomparisonsavailable inpython:<,>,>=(greater or equal),<=(less or equal),==(equal),!=(not equal) andis(identical)

Obviously, these operators and comparisons can be used within tremendously complex analyzes and actually build their basis.

Lets check them out further via a few quick examples, starting with operators:

[1 + 2,

1 - 2,

1 * 2,

1 / 2,

1 ** 2,

1 % 2]

[3, -1, 2, 0.5, 1, 1]

In Python 2.7, what kind of division (/) will be executed, depends on the type of the numbers involved. If all numbers are integers, the division will be an integer division, otherwise, it will be a float division. In Python 3 this has been changed and fractions aren’t lost when dividing integers (for integer division you can use another operator, //). In Python 3 the following two operations will give the same result (in Python 2 the first one will be treated as an integer division). It’s thus important to remember that the data type of division outcomes will always be float.

print(1 / 2)

print(1 / 2.0)

0.5

0.5

Python also respects arithemic rules, like the sequence of +/- and *//.

1 + 2/4

1.5

1 + 2 + 3/4

3.75

The same holds true for () and operators:

(1 + 2)/4

0.75

(1 + 2 + 3)/4

1.5

Thus, always watch out for how you define arithmetic operations!

Just as a reminder: the power operator in python is ** and not ^:

2 ** 2

4

This arithmetic operations also show some “handy” properties in combination with assignments, specifically you can apply these operations and modify the value of a given variable “in-place”. This means that you don’t have to assign a given variable a new value via an additional line like so:

a = 2

a = a * 2

print(a)

4

but you can shortcut the command a = a * 2 to a *= 2. This also works with other operators: +=, -= and /=.

b = 3

b *= 3

print(b)

9

Interestingly, we meet booleans again. This time in the form of operators. So booleans can not only be referred to as a data type but also operators. Whereas the data type entails the values True and False, the operators are spelled out as the words and, not, or. They therefore allow us to evaluate if

something

andsomething else is the casesomething is

notthe casesomething

orsomething else is the case

How about we check this on an example, i.e. the significance of our test results from the recap:

outcome_anova = True

outcome_ancova = False

outcome_anova and outcome_ancova

False

not outcome_ancova

True

outcome_anova or outcome_ancova

True

While the “classic” operators appear to be rather simple and the “boolean” operators rather abstract, a sufficient understanding of both is very important to efficiently utilize the python programming language. However, don’t worry: we’ll use them throughout the entire course going forward to gain further experience.

After spending a look at operators, it’s time to check out comparisons in more detail. Again, most of them might seem familiar and work as you would expect. Here’s the list again:

Comparisonsinpython>,<,>=(greater or equal),<=(less or equal),==(equal),!=(not equal) andis(identical)

The first four are the “classics” and something you might remember from your math classes in high school. Nevertheless, it’s worth to check how they exactly work in python.

If we compare numerical values, we obtain booleans that indicate if the comparisons is True or False. Lets start with the “classics”.

2 > 1, 2 < 1

(True, False)

2 > 2, 2 < 2

(False, False)

2 >= 2, 2 <= 2

(True, True)

So far so good and no major surprises. Now lets have a look at those comparisons that might be less familiar. At first, ==. You might think: “What, a double assignment?” but actually == is the equal comparison and thus compares two variables, numbers, etc., evaluating if they are equal to each other.

1 == 1

True

outcome_anova == outcome_ancova

False

'This course' == "cool"

False

1 == 1 == 2

False

One interesting thing to mention here is that equal values of different data types, i.e. integers and floats, are still evaluated as equal by ==:

1 == 1.0

True

Contrarily to evaluating if two or more things are equal via ==, we can utilize != to evaluate if two are more things are not equal. The behavior of these comparison concerning the outcome is however identical: we get booleans.

2 != 3

True

outcome_anova = True

outcome_ancova = False

outcome_anova != outcome_ancova

True

1 != 1 != 2

False

There’s actually one very specific comparison that only works for one data type: string comparison. The string comparison is reflected by the word in and evaluates if a string is part of another string. For example, you can evaluate if a word or certain string pattern is part of another string. Two fantastic beings are going to help showcasing this!

Please welcome, the Wombat & the Capybara.

"cool" in "Wombats are cool"

True

"ras ar" in "Wombats and capybaras are cool"

True

The string comparison can also be combined with the boolean operator to evaluate if a string or string pattern is not part of another string.

"stupid" not in "Wombats and capybaras"

True

Before we finish the operators & comparison part, it’s important to outline one important aspects that you’ve actually already seen here and there but was never mentioned/explained in detail: operators & comparisons work directly on variables, that is their values. For example, if we want to change the number of a variable called n_lectures from 5 to 6, we can simply run:

n_lectures = 5

n_lectures = n_lectures + 1

n_lectures

6

or use the shortcut as seen before

n_lectures = 5

n_lectures += 1

n_lectures

6

This works with other types and operators/comparisons too, for example strings and ==:

'Wombats' == 'Capybaras'

False

Exercise 4.1#

You want to compute the mean of the following reaction times: 1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7. Is there a way to achieve that using operators?

# Please write your solution here

(1.2 + 1.0 + 1.5 + 1.9 + 1.3 + 1.2 + 1.7)/7

Spoiler: there are of course many existing functions for all sorts of equations and statistics so you don’t have to write it yourself every time. For example, we could also compute the mean using numpy’s mean function:

import numpy as np

np.mean([1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7])

Exercise 4.2#

Having computed the mean, you need to compare it to a reference value. The latter can be possibly found in a string that entails data from a previous analyses. If that’s the case, the string should contain the words "mean reaction time". Is there a way to evaluate this?

The string would be: “In contrast to the majority of the prior studies the mean reaction time of the here described analyses was 1.2.”

# Please write your solution here

reference = "In contrast to the majority of the prior studies the mean reaction time of the here described analyses was `1.2`."

"mean reaction time" in reference

Exercise 4.3#

Having found the reference value, that is 1.2 we can compare it to our mean. Specifically, you want to know if the mean is less or equal than 1.2. The outcome of the comparison should then be the value of a new variable called mean_reference_comp.

# Please write your solution here

mean = (1.2 + 1.0 + 1.5 + 1.9 + 1.3 + 1.2 + 1.7)/7

mean_reference_comp = mean <= 1.2

mean_reference_comp

Fantastic work folks, really really great! Time for a quick party!

Having already checked out modules, help & descriptions, variables and data types, operators and comparisons, we will continue with the final section of the first block of our python introduction. More precisely, we will advance to new, more complex data types and structures: strings, lists, tuples and dictionaries.

Strings, List and dictionaries#

So far, we’ve explored integers, float, strings and boolean as fundamental types. However, there are a few more that are equally important within the python programing language and allow you to easily achieve complex behavoir and ease up your everyday programming life: strings, lists, tuples and dictionaries.

Strings#

Wait, what? Why are we talking about strings again? Well, actually, strings are more than a “just” fundamental type. There are quite a few things you can do with strings that we haven’t talked about yet. However, first things first: strings contain text:

statement = "The wombat and the capybara are equally cute. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america."

statement

'The wombat and the capybara are equally cute. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

type(statement)

str

So, what else can we do? For example, we can get the length of the string which reflects the number of characters in the string. The respective len function is one of the python functions that’s always available to you, even without importing it. Notably, len can operate on various data types which we will explore later.

len(statement)

135

The string data types also allows us to replace parts of it, i.e. substrings, with a different string. The respective syntax is string.replace("substring_to_replace", "replacement_string"), that is, .replace searches for "substring_to_replace" and replaces it with "replacement_string". If we for example want to state that wombats and capybaras are awesome instead of cute, we could do the following:

statement.replace("cute", "awesome")

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

Importantly, strings are not replaced in-place but require a new variable assignment.

statement

'The wombat and the capybara are equally cute. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

statement_2 = statement.replace("cute", "awesome")

statement_2

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

We can also index a string using string[x] to get the character at the specified index:

statement_2

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

statement_2[1]

'h'

Pump the breaks right there: why do we get h when we specify 1 as index? Shouldn’t this get us the first index and thus T?

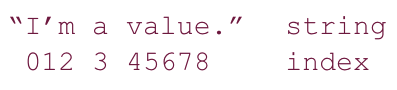

HEADS UP EVERYONE: INDEXING IN PYTHON STARTS AT 0

This means that the first index is 0, the second index 1, the third index 2, etc. . This holds true independent of the data type and is one of the major confusions when folks start programming in python, so always watch out!

statement_2

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

statement_2[0]

'T'

statement_2[1]

'h'

statement_2[2]

'e'

If we want to get more than one character of a string we can use the following syntax string[start:stop] which extracts characters between index start and stop. This technique is called slicing.

statement_2[4:10]

'wombat'

If we omit either (or both) of start or stop from [start:stop], the default is the beginning and the end of the string, respectively:

statement_2[:10]

'The wombat'

statement_2[10:]

' and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

statement_2[:]

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

We can also define the step size using the syntax [start:end:step] (the default value for step is 1, as we saw above):

statement_2[::1]

'The wombat and the capybara are equally awesome. However, while the wombat lives in Australia, the capybara can be found in south america.'

statement_2[::2]

'Tewma n h ayaaaeeulyaeoe oee,wietewma ie nAsrla h ayaacnb on nsuhaeia'

String formatting#

Besides operating on strings we can also apply different formatting styles. More precisely, this refers to different ways of displaying strings. The main function we’ll explore regarding this will be the print function. Comparable to len, it’s one of the python functions that’s always available to you, even without import.

For example, if we print strings added with +, they are concatenated without space:

print("The" + "results" + "were" + "significant")

Theresultsweresignificant

The print function concatenates strings differently, depending how the inputs are specified. If we just provide all strings without anything else, they will be concatenated without spaces:

print("The" "results" "were" "significant")

Theresultsweresignificant

If we provide strings separated by ,, they will be concatenated with spaces:

print("The", "results", "were", "significant")

The results were significant

Interestingly, the print function converts all inputs to strings, no matter their actual type:

print("The", "results", "were", "significant", 0.049, False)

The results were significant 0.049 False

Another very cool and handy option that we can specify placeholders which will be filled with an input according to a given formatting style. Python has two string formatting styles. An example of the old style is below, the placeholder or specifier %.3f transforms the input number into a string, that corresponds to a floating point number with 3 decimal places and the specifier %d transforms the input number into a string, corresponding to a decimal number.

print("The results were significant at %.3f" %(0.049))

The results were significant at 0.049

print("The results were significant at %d" %(0.049))

The results were significant at 0

As you can see, you have to be very careful with string formatting as important information might otherwise get lost!

We can achieve the same outcome using the new style string formatting which uses {} followed by .format().

print("The results were significant at {:.3f}" .format(0.049))

The results were significant at 0.049

If you would like to include line-breaks and/or tabs in your strings, you can use \n and \t respectively:

print("Geez, there are some many things \nPython can do with \t strings.")

Geez, there are some many things

Python can do with strings.

We can of course also combine the different string formatting options:

print("Animal: {}\nHabitat: {}\nRating: {}".format("Wombat", "Australia", 5))

Animal: Wombat

Habitat: Australia

Rating: 5

Single Quote#

You can specify strings using single quotes such as 'Quote me on this'.

All white space i.e. spaces and tabs, within the quotes, are preserved as-is.

Double Quotes#

Strings in double quotes work exactly the same way as strings in single quotes. An example is "What's your name?".

Triple Quotes#

You can specify multi-line strings using triple quotes - (""" or '''). You can use single quotes and double quotes freely within the triple quotes. An example is:

'''I'm the first line. Check how line-breaks are shown in the second line.

Do you see the line-break?

"What's going on here?," you might ask.

Well, "that's just how tiple quotes work."

'''

'I\'m the first line. Check how line-breaks are shown in the second line.\nDo you see the line-break?\n"What\'s going on here?," you might ask.\nWell, "that\'s just how tiple quotes work."\n'

Exercise 5.1#

Create two variables called info_wombat and info_capybara and provide them the following values respectively:

“The wombat is quadrupedal marsupial and can weigh up to 35 kg.”

“The capybara is the largest rodent on earth. Its relatives include the guinea pig and the chinchilla.”

Once created, please verify that the type is string.

# Please write your solution here

info_wombat = "The wombat is quadrupedal marsupial and can weigh up to 35 kg."

info_capybara = "The capybara is the largest rodent on earth. Its relatives include the guinea pig and the chinchilla."

print(type(info_wombat))

print(type(info_capybara))

Exercise 5.2#

Compute the length and print within the strings “The wombat information has [insert length here] characters.” and “The capybara information has [insert length here] characters.” After that, please compare the length of the strings and print if they are equal.

# Please write your solution here

print("The wombat information has %s characters." %len(info_wombat))

print("The capybara information has %s characters." %len(info_capybara))

print("The information has an equal amount of characters: %s" %str(len(info_wombat)==len(info_capybara)))

Exercise 5.3#

Get the following indices from the info_wombat and info_capybara respectively: 4-10 and 4-12. Replace the resulting word in info_wombat with capybara and the resulting word in info_capybara with wombat.

print(info_wombat[4:10])

print(info_capybara[4:12])

print(info_wombat.replace('wombat', 'capybara'))

print(info_capybara.replace('capybara', 'wombat'))

List#

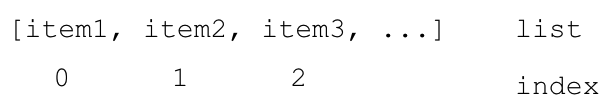

Next up: lists. In general, lists are very similar to strings. One crucial difference is that list elements (things in the list) can be of any type: integers, floats, strings, etc. . Additionally, types can be freely mixed within a list, that is, each element of a list can be of a different type. Lists are among the data types and structures you’ll work with almost every time you do something in python. They are super handy and comparably to strings, have a lot of “in-built” functionality.

The basic syntax for creating lists in python is [...]:

[1,2,3,4]

[1, 2, 3, 4]

type([1,2,3,4])

list

You can of course also set lists as the value of a variable. For example, we can create a list with our reaction times from before:

reaction_times = [1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7]

print(type(reaction_times))

print(reaction_times)

<class 'list'>

[1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7]

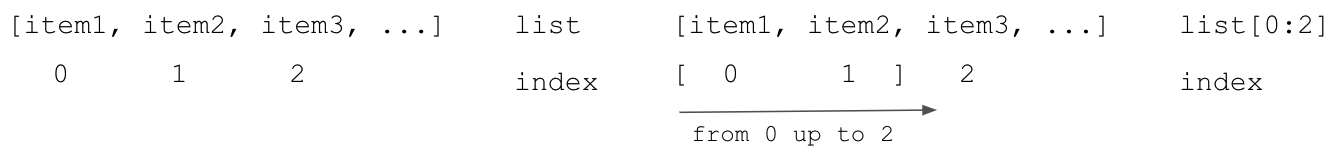

Going back to the comparison with strings, we can use the same index and slicing techniques to manipulate lists as we could use on strings: list[index], list[start:stop].

print(reaction_times)

print(reaction_times[1:3])

print(reaction_times[::2])

[1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7]

[1.0, 1.5]

[1.2, 1.5, 1.3, 1.7]

HEADS UP EVERYONE: INDEXING IN PYTHON STARTS AT 0

This means that the first index is 0, the second index 1, the third index 2, etc. . This holds true independent of the data type and is one of the major confusions when folks start programming in python, so always watch out!

Thus, to get the first index of our reaction_times, we have to do the following:

reaction_times[0]

1.2

There’s another important aspect related to index and slicing. Have a look at the following example that should get us the reaction times from index 1 to 4:

print(reaction_times)

print(reaction_times[1:4])

[1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7]

[1.0, 1.5, 1.9]

Isn’t there something missing, specifically the last index we wanted to grasp, i.e. 4?

HEADS UP EVERYONE: SLICING IN PYTHON EXCLUDES THE “STOP” INDEX

This means that the slicing technique gives you everything up to the stop index but does not include the stop index itself. For example, reaction_times[1:4] will return the list elements from index 1 up to 4 but not the fourth index. This holds true independent of the data type and is one of the major confusions when folks start programming in python, so always watch out!

So, to get to list elements from index 0 - 4, including 4, we have to do the following:

print(reaction_times)

print(reaction_times[0:5])

[1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3, 1.2, 1.7]

[1.2, 1.0, 1.5, 1.9, 1.3]

As mentioned before, elements in a list do not all have to be of the same type:

mixed_list = [1, 'a', 4.0, 'What is happening?']

print(mixed_list)

[1, 'a', 4.0, 'What is happening?']

Another nice thing to know: python lists can be inhomogeneous and arbitrarily nested, meaning that we can define and access lists within lists. Is this list-ception??

nested_list = [1, [2, [3, [4, [5]]]]]

print("our nest list looks like this: %s" %nested_list)

print("the length of our nested list is: %s" %len(nested_list))

print("the first index of our nested_list is: %s" %nested_list[0])

print("the second index of our nested_list is: %s" %nested_list[1])

print("the second index of our nested_list is a list we can index again via nested_list[1][1]: %s" %nested_list[1][1])

our nest list looks like this: [1, [2, [3, [4, [5]]]]]

the length of our nested list is: 2

the first index of our nested_list is: 1

the second index of our nested_list is: [2, [3, [4, [5]]]]

the second index of our nested_list is a list we can index again via nested_list[1][1]: [3, [4, [5]]]

Lets have a look at another list. Assuming you obtain data describing the favorite movies and snacks of a sample population, we can put the respective responses in lists for easy handling:

movies = ['The_Intouchables', 'James Bond', 'Forrest Gump', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'The Imitation Game',

'The Philosophers', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'Shutter Island', 'Love actually', 'The Great Gatsby',

'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'Fight Club', 'Shutter Island',

'Harry Potter', 'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince', 'Shindlers List', 'Inception']

snacks = ['pancakes', 'Banana', 'dominoes', 'carrots', 'hummus', 'chocolate', 'chocolate', 'Pringles', 'snickers',

'chocolate','Kinder bueno', 'sushi', 'mint chocolate', 'fruit', 'dried mango', 'dark chocolate',

'too complicated', 'snickers', 'Rocher']

A smaller subsample also provided their favorite animal. (If you also provided one but it doesn’t show up it means that you most likely used the “add attachment” option to add images or a way to refers to local files but doesn’t embed them directly in the notebook. Unfortunately, things can be a bit strange there…so don’t worry, we address this in subsequent sessions.)

animals = ['cat', 'lizard', 'coral', 'elephant', 'barred owl', 'groundhog']

So lets check what we can do with these lists. At first, here they are again:

print('The favorite movies were: %s' %movies)

print('\n')

print('The favorite snacks were: %s'%snacks)

print('\n')

print('The favorite animals were: %s' %animals)

The favorite movies were: ['The_Intouchables', 'James Bond', 'Forrest Gump', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Philosophers', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'Shutter Island', 'Love actually', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'Fight Club', 'Shutter Island', 'Harry Potter', 'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince', 'Shindlers List', 'Inception']

The favorite snacks were: ['pancakes', 'Banana', 'dominoes', 'carrots', 'hummus', 'chocolate', 'chocolate', 'Pringles', 'snickers', 'chocolate', 'Kinder bueno', 'sushi', 'mint chocolate', 'fruit', 'dried mango', 'dark chocolate', 'too complicated', 'snickers', 'Rocher']

The favorite animals were: ['cat', 'lizard', 'coral', 'elephant', 'barred owl', 'groundhog']

Initially we might want to count how many responses there were. We can achieve this via our old friend the len function. If we want to also check if we got responses from all 19 participants of our sample population, we can directly use comparisons.

print('Regarding movies there were %s responses' %len(movies))

print('We got responses from all participants: %s' %str(len(movies)==19))

Regarding movies there were 19 responses

We got responses from all participants: True

We can do the same for snacks and animals:

print('Regarding snacks there were %s responses' %len(snacks))

print('We got responses from all participants: %s' %str(len(snacks)==19))

Regarding snacks there were 19 responses

We got responses from all participants: True

print('Regarding animals there were %s responses' %len(animals))

print('We got responses from all participants: %s' %str(len(animals)==19))

Regarding animals there were 6 responses

We got responses from all participants: False

Another thing we might want to check is the number of unique responses, that is if some values in our list appear multiple times and we might also want to get these values. In python we have various ways to do this, most often you’ll see (and most likely use) set and numpy’s unique functions. While the first is another example of in-built python functions that don’t need to be imported, the second is a function of the numpy module. They however can achieve the same goal, that is getting us the number of unique values.

print('There are %s unique responses regarding movies' %len(set(movies)))

There are 17 unique responses regarding movies

import numpy as np

print('There are %s unique responses regarding movies' %len(np.unique(movies)))

There are 17 unique responses regarding movies

The functions themselves will also give us the list of unique values:

import numpy as np

print('The unique responses regarding movies were: %s' %np.unique(movies))

The unique responses regarding movies were: ['Call Me by Your Name' 'Fight Club' 'Forrest Gump' 'Harry Potter'

'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince' 'Inception' 'Interstellar'

'James Bond' 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers' 'Love actually'

'Retired Extremely Dangerous' 'Shindlers List' 'Shutter Island'

'The Great Gatsby' 'The Imitation Game' 'The Philosophers'

'The_Intouchables']

Doing the same for snacks and animals again is straightforward:

print('There are %s unique responses regarding snacks' %len(np.unique(snacks)))

print('The unique responses regarding snacks were: %s' %np.unique(snacks))

There are 16 unique responses regarding snacks

The unique responses regarding snacks were: ['Banana' 'Kinder bueno' 'Pringles' 'Rocher' 'carrots' 'chocolate'

'dark chocolate' 'dominoes' 'dried mango' 'fruit' 'hummus'

'mint chocolate' 'pancakes' 'snickers' 'sushi' 'too complicated']

print('There are %s unique responses regarding animals' %len(np.unique(animals)))

print('The unique responses regarding animals were: %s' %np.unique(animals))

There are 6 unique responses regarding animals

The unique responses regarding animals were: ['barred owl' 'cat' 'coral' 'elephant' 'groundhog' 'lizard']

In-built functions#

As indicated before, lists have a great set of in-built functions that allow to perform various operations/transformations on them: sort, append, insert and remove. Please note, as these functions are part of the data type “list”, you don’t prepend (sort(list)) but append them: list.sort(), list.append(), list.insert() and list.remove().

Lets start with sort which, as you might have expected, will sort our list.

movies.sort()

movies

['Call Me by Your Name',

'Fight Club',

'Forrest Gump',

'Harry Potter',

'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince',

'Inception',

'Inception',

'Interstellar',

'James Bond',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'Love actually',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Shindlers List',

'Shutter Island',

'Shutter Island',

'The Great Gatsby',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Philosophers',

'The_Intouchables']

Please note that our list is modified/changed in-place. While it’s nice to not have to do a new assignment, this can become problematic if the index is of relevance!

.sort() also allows you to specify how the list should be sorted: ascending or descending. This is controlled via the reverse argument of the .sort() function. By default, lists are sorted in an descending order. If you want to sort your list in an ascending order you have to set the reverse argument to True: list.sort(reverse=True).

movies.sort(reverse=True)

movies

['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name']

We of course also want to sort our lists of snacks and animals:

snacks.sort()

snacks

['Banana',

'Kinder bueno',

'Pringles',

'Rocher',

'carrots',

'chocolate',

'chocolate',

'chocolate',

'dark chocolate',

'dominoes',

'dried mango',

'fruit',

'hummus',

'mint chocolate',

'pancakes',

'snickers',

'snickers',

'sushi',

'too complicated']

animals.sort()

animals

['barred owl', 'cat', 'coral', 'elephant', 'groundhog', 'lizard']

Lets assume we got new data from two participants and thus need to update our list, we can simply use .append() to, well, append or add these new entries:

movies.append('My Neighbor Totoro')

movies

['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name',

'My Neighbor Totoro']

We obviously do the same for snacks and animals again:

snacks.append('Wasabi Peanuts')

snacks

['Banana',

'Kinder bueno',

'Pringles',

'Rocher',

'carrots',

'chocolate',

'chocolate',

'chocolate',

'dark chocolate',

'dominoes',

'dried mango',

'fruit',

'hummus',

'mint chocolate',

'pancakes',

'snickers',

'snickers',

'sushi',

'too complicated',

'Wasabi Peanuts']

animals.append('bear')

animals

['barred owl', 'cat', 'coral', 'elephant', 'groundhog', 'lizard', 'bear']

Should the index of the new value be important, you have to use .insert as .append will only ever, you guessed it: append. The .insert functions takes two arguments, the index where a new value should be inserted and the value that should be inserted: list.insert(index, value). The index of the subsequent values will shift +1 accordingly. Assuming, we want to add a new value at the third index of each of our lists, this how we would do that:

movies.insert(2, 'The Big Lebowski')

print(movies)

['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']

snacks.insert(2, 'PB&J')

print(snacks)

['Banana', 'Kinder bueno', 'PB&J', 'Pringles', 'Rocher', 'carrots', 'chocolate', 'chocolate', 'chocolate', 'dark chocolate', 'dominoes', 'dried mango', 'fruit', 'hummus', 'mint chocolate', 'pancakes', 'snickers', 'snickers', 'sushi', 'too complicated', 'Wasabi Peanuts']

animals.insert(2, 'Manatee')

print(animals)

['barred owl', 'cat', 'Manatee', 'coral', 'elephant', 'groundhog', 'lizard', 'bear']

If you want to change the value of a list element (e.g. you noticed an error and need to change the value), you can do that directly by assigning a new value to the element at the given index:

print('The element at index 15 of the list movies is: %s\n' %movies[15])

movies[15] = 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince'

print('It is now %s\n' %movies[15])

print(movies)

The element at index 15 of the list movies is: Harry Potter and the Halfblood Prince

It is now Harry Potter and the Python-Prince

['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']

Please note that this is final and the original value overwritten. The characteristic of modifying lists by assigning new values to elements in the list is called mutable in technical jargon.

If you want to remove an element of a given list (e.g. you noticed there are unwanted duplicates, etc.), you basically have two options list.remove(element) and del list[index] and which one you have to use depends on the goal. As you can see .remove(element) expects the element that should be removed from the list, that is the element with the specified value. For example, if we want to remove the duplicate Shutter Island, we can do the following:

movies.remove("Shutter Island")

print(movies)

['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']

As you can see, only one “Shutter Island” is removed and not both, this is because .remove(element) only removes the first element of the specified value. Thus, if there are more elements you want to remove, the del function could be more handy.

You may have noticed that the del function expects the index of the element that should be removed from the list. Thus, if we, for example, want to remove the duplicate Inception, we can also achieve that via the following:

del movies[12]

print(movies)

['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']

If there are multiple elements you want to remove, you can make use of slicing again. For example, our snack list has multiple elements with the value chocolate. Nothing against chocolate, but you might want to have this value only once in our list. To achieve that, we basically combine slicing and del via indicating what indices should be removed:

del snacks[7:9]

print(snacks)

['Banana', 'Kinder bueno', 'PB&J', 'Pringles', 'Rocher', 'carrots', 'chocolate', 'dark chocolate', 'dominoes', 'dried mango', 'fruit', 'hummus', 'mint chocolate', 'pancakes', 'snickers', 'snickers', 'sushi', 'too complicated', 'Wasabi Peanuts']

Lists play a very important role in python and are for example used in loops and other flow control structures (discussed in the next session). There are a number of convenient functions for generating lists of various types, for example, the range function (note that in Python 3 range creates a generator, so you have to use the list function to convert the output to a list). Creating a list that ranges from 10 to 50 advancing in steps of 2 is as easy as:

start = 10

stop = 50

step = 2

list(range(start, stop, step))

[10,

12,

14,

16,

18,

20,

22,

24,

26,

28,

30,

32,

34,

36,

38,

40,

42,

44,

46,

48]

This can be very handy if you want to create participant lists and/or condition lists for your experiment and/or analyzes.

Exercise 6.1#

Create a variable called rare_animals that stores the following values: ‘Addax’, ‘Black-footed Ferret’, ‘Northern Bald Ibis’, ‘Cross River Gorilla’, ‘Saola’, ‘Amur Leopard’, ‘Philippine Crocodile’, ‘Sumatran Rhino’, ‘South China Tiger’, ‘Vaquita’. After that, please count how many elements the list has and provide the info within the following statement: “There are [insert number of elements here] animals in the list.”

# Please write your solution here

rare_animals = ['Addax', 'Black-footed Ferret', 'Northern Bald Ibis', 'Cross River Gorilla', 'Saola', 'Amur Leopard', 'Philippine Crocodile', 'Sumatran Rhino', 'South China Tiger', 'Vaquita']

print("There are %s animals in the list." %len(rare_animals))

Exercise 6.2#

Please add ‘Manatee’ to the list and subsequently evaluate how many unique elements the list has.

# Please write your solution here

rare_animals.append('Manatee')

len(set(rare_animals))

Exercise 6.3#

Learning that the manatee is not endangered anymore, please remove it from the list. Unfortunately, we have to add “Giant Panda”. Could you please do that at index 3.

# Please write your solution here

rare_animals.remove('Manatee') # or del rare_animals[11]

rare_animals.insert(2, 'Giant Panda')

rare_animals

Tuples#

Tuples are like lists, except that they cannot be modified once created, that is they are immutable.

In python, tuples are created using the syntax (..., ..., ...), or even ..., ...:

point = (10, 20, 'Whoa another thing')

print(type(point))

print(point)

<class 'tuple'>

(10, 20, 'Whoa another thing')

Elements of tuples can also be referenced via their respective index:

print(point[0])

print(point[1])

print(point[2])

10

20

Whoa another thing

However, as mentioned above, if we try to assign a new value to an element in a tuple we get an error:

try:

point[0] = 20

except(TypeError) as er:

print("TypeError:", er)

else:

raise

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

Thus, tuples also don’t have the set of functions to modify elements lists do.

Exercise 7.1#

Please create a tuple called deep_thought with the following values: ‘answer’, 42.

# Please write your solution here

deep_thought = ('answer', 42)

deep_thought

Dictionaries#

Dictionaries are also like lists, except that each element is a key-value pair. That is, elements or entries of the dictionary, the values, can only be assessed via their respective key and not via indexing, slicing, etc. .

The syntax for dictionaries is {key1 : value1, ...}.

Dictionaries are fantastic if you need to organize your data in a highly structured way where a precise mapping of a multiple of types is crucial and lists might be insufficient. For example, we want to have the information we assessed above for our lists in a detailed and holistic manner. Instead of specifying multiple lists and variables, we could also create a dictionary that comprises all of that information.

movie_info = {"n_responses" : len(movies),

"n_responses_unique" : len(set(movies)),

"responses" : movies}

print(type(movie_info))

print(movie_info)

<class 'dict'>

{'n_responses': 19, 'n_responses_unique': 19, 'responses': ['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']}

See how great this is? We have everything in one place and can access the information we need/want via the respective key.

movie_info['n_responses']

19

movie_info['n_responses_unique']

19

movie_info['responses']

['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Big Lebowski',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name',

'My Neighbor Totoro']

As you can see and mentioned before: like lists, each value of a dictionary can entail various types: integer, float, string and even data types: lists, tuples, etc. . However, in contrast to lists, we can access entries can only via their key name and not indices:

movie_info[1]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[139], line 1

----> 1 movie_info[1]

KeyError: 1

If you try that, you’ll get a KeyError indicating that the key whose value you want to access doesn’t exist.

If you’re uncertain about the keys in your dictionary, you can get a list of all of them via dictionary.keys():

movie_info.keys()

dict_keys(['n_responses', 'n_responses_unique', 'responses'])

Comparably, if you want to get all the values, you can use dictionary.values() to obtain a respective list:

movie_info.values()

dict_values([19, 19, ['The_Intouchables', 'The Philosophers', 'The Big Lebowski', 'The Imitation Game', 'The Great Gatsby', 'Shutter Island', 'Shindlers List', 'Retired Extremely Dangerous', 'Love actually', 'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers', 'James Bond', 'Interstellar', 'Inception', 'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince', 'Harry Potter', 'Forrest Gump', 'Fight Club', 'Call Me by Your Name', 'My Neighbor Totoro']])

Assuming you want to add new information to your dictionary, i.e. a new key, this can directly be done via dictionary[new_key] = value. For example, you run some stats on our list of movies and determined that this selection is significantly awesome with a p value of 0.000001, we can easily add this to our dictionary:

movie_info['movie_selection_awesome'] = True

movie_info['movie_selection_awesome_p_value'] = 0.000001

movie_info

{'n_responses': 19,

'n_responses_unique': 19,

'responses': ['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Big Lebowski',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name',

'My Neighbor Totoro'],

'movie_selection_awesome': True,

'movie_selection_awesome_p_value': 1e-06}

As with lists, the value of a given element, here entry can be modified and deleted. This means they are mutable. If we for example forgot to correct our p value for multiple comparisons, we can simply overwrite the original with corrected one:

movie_info['movie_selection_awesome_p_value'] = 0.001

movie_info

{'n_responses': 19,

'n_responses_unique': 19,

'responses': ['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Big Lebowski',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name',

'My Neighbor Totoro'],

'movie_selection_awesome': True,

'movie_selection_awesome_p_value': 0.001}

Assuming we then want to delete the p value from our dictionary because we remembered that the sole focus on significance and p values brought the entirety of science down to a very bad place, we can achieve this via:

del movie_info['movie_selection_awesome_p_value']

movie_info

{'n_responses': 19,

'n_responses_unique': 19,

'responses': ['The_Intouchables',

'The Philosophers',

'The Big Lebowski',

'The Imitation Game',

'The Great Gatsby',

'Shutter Island',

'Shindlers List',

'Retired Extremely Dangerous',

'Love actually',

'Lord of the Rings - The Two Towers',

'James Bond',

'Interstellar',

'Inception',

'Harry Potter and the Python-Prince',

'Harry Potter',

'Forrest Gump',

'Fight Club',

'Call Me by Your Name',

'My Neighbor Totoro'],

'movie_selection_awesome': True}

Exercise 8.1#

Oh damn, we completely forgot to create a comparable dictionary for our snacks list. How would create one that follows the example from the movie list? NB: you can skip the p value right away:

# Please write your solution here

snack_info = {"n_responses" : len(snacks),

"n_responses_unique" : len(set(snacks)),

"responses" : snacks,

"snack_selection_awesome": True}

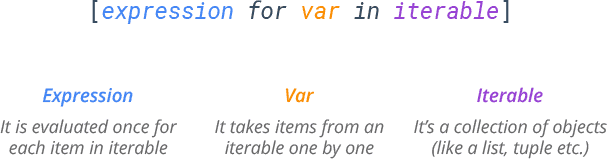

print(type(snack_info))