Introduction to the jupyter ecosystem & notebooks¶

Before we get started 1…¶

most of what you’ll see within this lecture was prepared by Ross Markello, Michael Notter and Peer Herholz and further adapted for this course by Peer Herholz

based on Tal Yarkoni’s “Introduction to Python” lecture at Neurohackademy 2019

based on http://www.stavros.io/tutorials/python/ & http://www.swaroopch.com/notes/python

based on https://github.com/oesteban/biss2016 & https://github.com/jvns/pandas-cookbook

Goals¶

learn basic and efficient usage of the

jupyter ecosystem¬ebookswhat is

Jupyter& how to utilizejupyter notebooks

To Jupyter & beyond¶

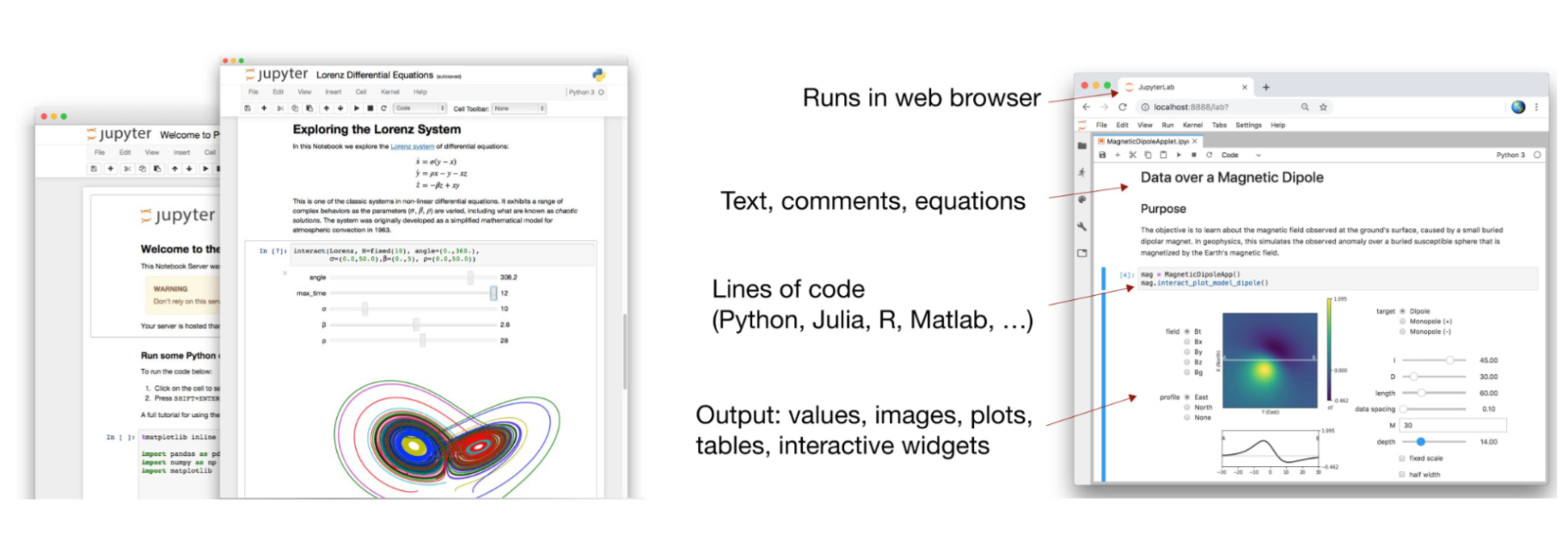

a community of people

an ecosystem of open tools and standards for interactive computing

language-agnostic and modular

empower people to use other open tools

To Jupyter & beyond¶

Before we get started 2…¶

We’re going to be working in Jupyter notebooks for most of this presentation!

To load yours, do the following:

Open a terminal

Type

jupyter notebook

If you’re not automatically directed to a webpage copy the URL printed in the terminal and paste it in your browser

Click “New” in the top-right corner and select “Python 3”

You have a Jupyter notebook!

Files Tab¶

The files tab provides an interactive view of the portion of the filesystem which is accessible by the user. This is typically rooted by the directory in which the notebook server was started.

The top of the files list displays clickable breadcrumbs of the current directory. It is possible to navigate the filesystem by clicking on these breadcrumbs or on the directories displayed in the notebook list.

A new notebook can be created by clicking on the New dropdown button at the top of the list, and selecting the desired language kernel.

Notebooks can also be uploaded to the current directory by dragging a notebook file onto the list or by clicking the Upload button at the top of the list.

The Notebook¶

When a notebook is opened, a new browser tab will be created which presents the notebook user interface (UI). This UI allows for interactively editing and running the notebook document.

A new notebook can be created from the dashboard by clicking on the Files tab, followed by the New dropdown button, and then selecting the language of choice for the notebook.

An interactive tour of the notebook UI can be started by selecting Help -> User Interface Tour from the notebook menu bar.

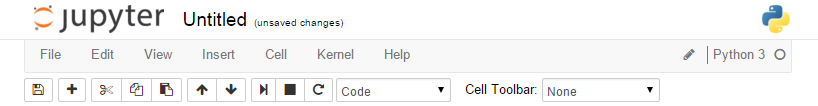

Header¶

At the top of the notebook document is a header which contains the notebook title, a menubar, and toolbar. This header remains fixed at the top of the screen, even as the body of the notebook is scrolled. The title can be edited in-place (which renames the notebook file), and the menubar and toolbar contain a variety of actions which control notebook navigation and document structure.

Body¶

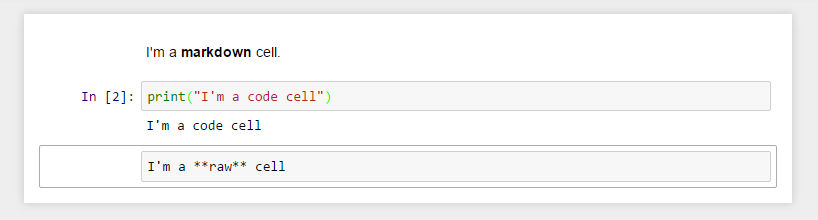

The body of a notebook is composed of cells. Each cell contains either markdown, code input, code output, or raw text. Cells can be included in any order and edited at-will, allowing for a large amount of flexibility for constructing a narrative.

Markdown cells- These are used to build anicely formatted narrativearound thecodein the document. The majority of this lesson is composed ofmarkdown cells.Code cells- These are used to define thecomputational codein thedocument. They come intwo forms:the

input cellwhere theusertypes thecodeto beexecuted,and the

output cellwhich is therepresentationof theexecuted code. Depending on thecode, thisrepresentationmay be asimple scalar value, or something more complex like aplotor aninteractive widget.

Raw cells- These are used whentextneeds to be included inraw form, withoutexecutionortransformation.

Modality¶

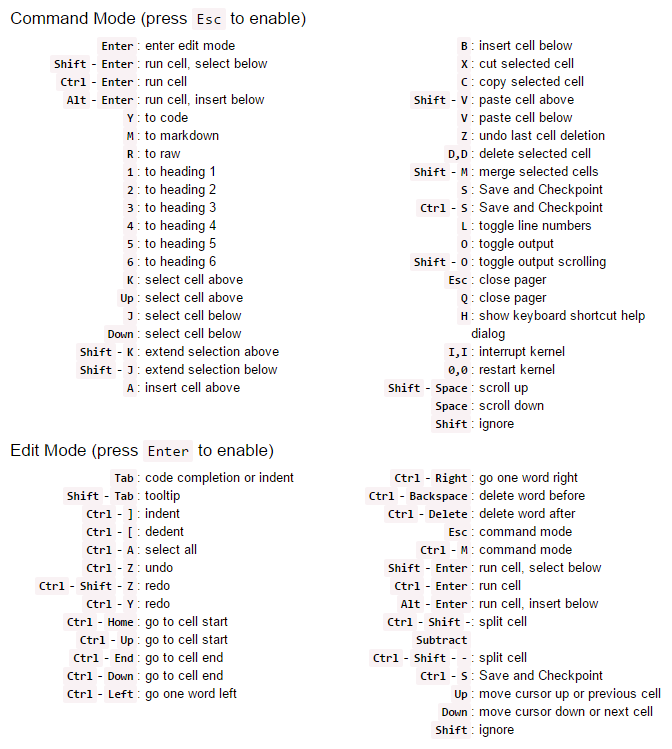

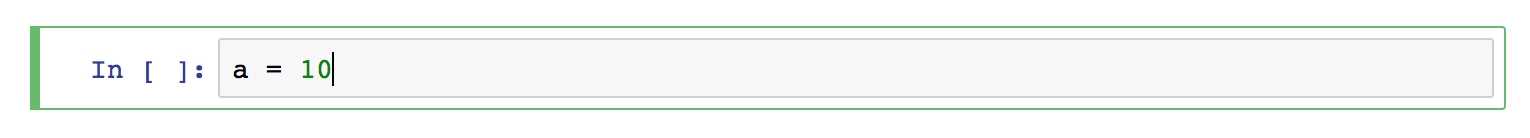

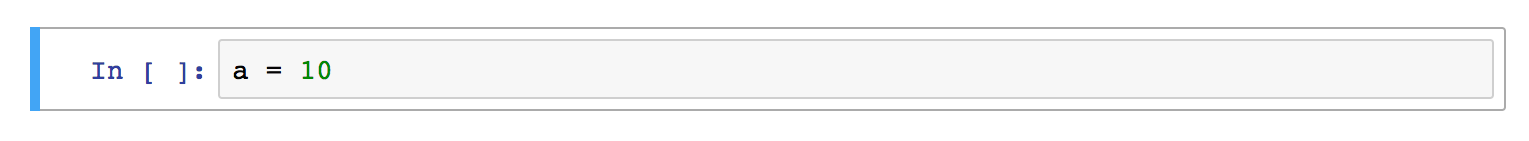

The notebook user interface is modal. This means that the keyboard behaves differently depending upon the current mode of the notebook. A notebook has two modes: edit and command.

Edit mode is indicated by a green cell border and a prompt showing in the editor area. When a cell is in edit mode, you can type into the cell, like a normal text editor.

Command mode is indicated by a grey cell border. When in command mode, the structure of the notebook can be modified as a whole, but the text in individual cells cannot be changed. Most importantly, the keyboard is mapped to a set of shortcuts for efficiently performing notebook and cell actions. For example, pressing c when in command mode, will copy the current cell; no modifier is needed.

Markdown Cells¶

Text can be added to IPython Notebooks using Markdown cells. Markdown is a popular markup language that is a superset of HTML. Its specification can be found here:

http://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/

You can view the source of a cell by double clicking on it, or while the cell is selected in command mode, press Enter to edit it. Once a cell has been edited, use Shift-Enter to re-render it.

Markdown basics¶

You can make text italic or bold.

You can build nested itemized or enumerated lists:

One

Sublist

This

Sublist - That - The other thing

Two

Sublist

Three

Sublist

Now another list:

Here we go

Sublist

Sublist

There we go

Now this

You can add horizontal rules:

Here is a blockquote:

Beautiful is better than ugly. Explicit is better than implicit. Simple is better than complex. Complex is better than complicated. Flat is better than nested. Sparse is better than dense. Readability counts. Special cases aren’t special enough to break the rules. Although practicality beats purity. Errors should never pass silently. Unless explicitly silenced. In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess. There should be one– and preferably only one –obvious way to do it. Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you’re Dutch. Now is better than never. Although never is often better than right now. If the implementation is hard to explain, it’s a bad idea. If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea. Namespaces are one honking great idea – let’s do more of those!

You can add headings using Markdown’s syntax:

# Heading 1 # Heading 2 ## Heading 2.1 ## Heading 2.2

Embedded code¶

You can embed code meant for illustration instead of execution in Python:

def f(x):

"""a docstring"""

return x**2

or other languages:

if (i=0; i<n; i++) {

printf("hello %d\n", i);

x += 4;

}

Github flavored markdown (GFM)¶

The Notebook webapp support Github flavored markdown meaning that you can use triple backticks for code blocks

```python

print "Hello World"

```

```javascript

console.log("Hello World")

```

Gives

print "Hello World"

console.log("Hello World")

And a table like this :

| This | is | |------|------| | a | table|

A nice HTML Table

This |

is |

|---|---|

a |

table |

General HTML¶

Because Markdown is a superset of HTML you can even add things like HTML tables:

| Header 1 | Header 2 |

|---|---|

| row 1, cell 1 | row 1, cell 2 |

| row 2, cell 1 | row 2, cell 2 |

Local files¶

If you have local files in your Notebook directory, you can refer to these files in Markdown cells directly:

[subdirectory/]<filename>

For example, in the static folder, we have the logo:

<img src="static/nipy_logo.png" />

These do not embed the data into the notebook file, and require that the files exist when you are viewing the notebook.

Security of local files¶

Note that this means that the IPython notebook server also acts as a generic file server for files inside the same tree as your notebooks. Access is not granted outside the notebook folder so you have strict control over what files are visible, but for this reason it is highly recommended that you do not run the notebook server with a notebook directory at a high level in your filesystem (e.g. your home directory).

When you run the notebook in a password-protected manner, local file access is restricted to authenticated users unless read-only views are active.

Markdown attachments¶

Since Jupyter notebook version 5.0, in addition to referencing external files you can attach a file to a markdown cell. To do so drag the file from e.g. the browser or local storage in a markdown cell while editing it

Files are stored in cell metadata and will be automatically scrubbed at save-time if not referenced. You can recognize attached images from other files by their url that starts with attachment. For the image above:

Keep in mind that attached files will increase the size of your notebook.

You can manually edit the attachement by using the View > Cell Toolbar > Attachment menu, but you should not need to.

Code cells¶

When executing code in IPython, all valid Python syntax works as-is, but IPython provides a number of features designed to make the interactive experience more fluid and efficient. First, we need to explain how to run cells. Try to run the cell below!

import pandas as pd

print("Hi! This is a cell. Click on it and press the ▶ button above to run it")

You can also run a cell with Ctrl+Enter or Shift+Enter. Experiment a bit with that.

Tab Completion¶

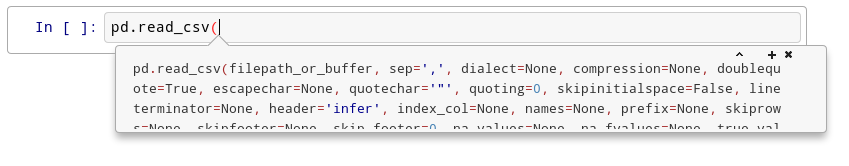

One of the most useful things about Jupyter Notebook is its tab completion.

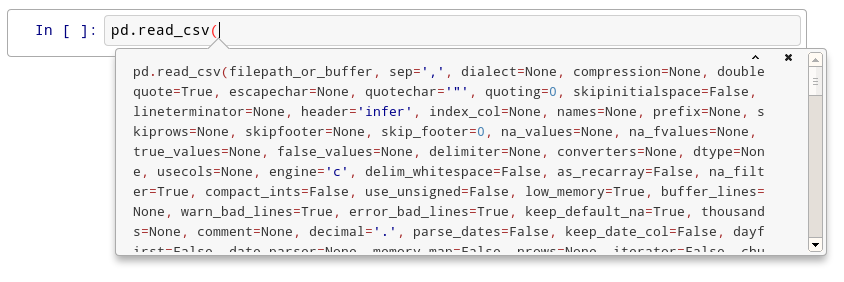

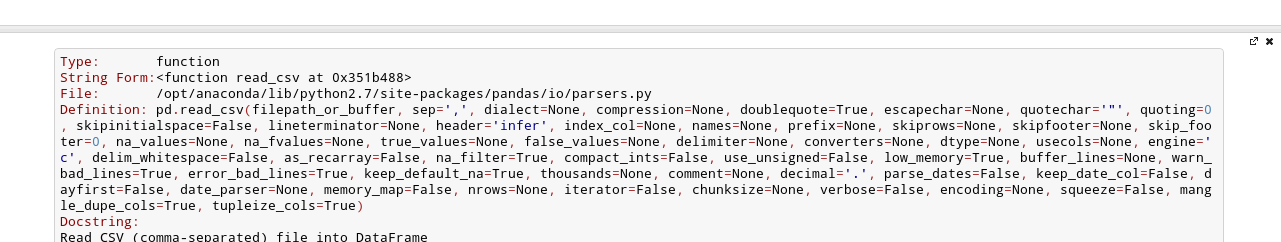

Try this: click just after read_csv( in the cell below and press Shift+Tab 4 times, slowly. Note that if you’re using JupyterLab you don’t have an additional help box option.

pd.read_csv(

After the first time, you should see this:

After the second time:

After the fourth time, a big help box should pop up at the bottom of the screen, with the full documentation for the read_csv function:

This is amazingly useful. You can think of this as “the more confused I am, the more times I should press Shift+Tab”.

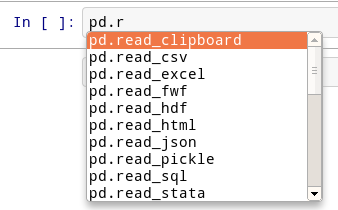

Okay, let’s try tab completion for function names!

pd.r

You should see this:

Get Help¶

There’s an additional way on how you can reach the help box shown above after the fourth Shift+Tab press. Instead, you can also use obj? or obj?? to get help or more help for an object.

pd.read_csv?

Writing code¶

Writing code in a notebook is pretty normal.

def print_10_nums():

for i in range(10):

print(i)

print_10_nums()

If you messed something up and want to revert to an older version of a code in a cell, use Ctrl+Z or to go than back Ctrl+Y.

For a full list of all keyboard shortcuts, click on the small keyboard icon in the notebook header or click on Help > Keyboard Shortcuts.

The interactive workflow: input, output, history¶

Notebooks provide various options for inputs and outputs, while also allowing to access the history of run commands.

2+10

_+10

You can suppress the storage and rendering of output if you append ; to the last cell (this comes in handy when plotting with matplotlib, for example):

10+20;

_

The output is stored in _N and Out[N] variables:

_9 == Out[9]

Previous inputs are available, too:

In[10]

_i

%history -n 1-5

Accessing the underlying operating system¶

Through notebooks you can also access the underlying operating system and communicate with it as you would do in e.g. a terminal via bash:

!pwd

files = !ls

print("My current directory's files:")

print(files)

!echo $files

!echo {files[0].upper()}

Magic functions¶

IPython has all kinds of magic functions. Magic functions are prefixed by % or %%, and typically take their arguments without parentheses, quotes or even commas for convenience. Line magics take a single % and cell magics are prefixed with two %%.

Some useful magic functions are:

Magic Name |

Effect |

|---|---|

%env |

Get, set, or list environment variables |

%pdb |

Control the automatic calling of the pdb interactive debugger |

%pylab |

Load numpy and matplotlib to work interactively |

%%debug |

Activates debugging mode in cell |

%%html |

Render the cell as a block of HTML |

%%latex |

Render the cell as a block of latex |

%%sh |

%%sh script magic |

%%time |

Time execution of a Python statement or expression |

You can run %magic to get a list of magic functions or %quickref for a reference sheet.

%magic

Line vs cell magics:

%timeit list(range(1000))

%%timeit

list(range(10))

list(range(100))

Line magics can be used even inside code blocks:

for i in range(1, 5):

size = i*100

print('size:', size, end=' ')

%timeit list(range(size))

Magics can do anything they want with their input, so it doesn’t have to be valid Python:

%%bash

echo "My shell is:" $SHELL

echo "My disk usage is:"

df -h

Another interesting cell magic: create any file you want locally from the notebook:

%%writefile test.txt

This is a test file!

It can contain anything I want...

And more...

!cat test.txt

Let’s see what other magics are currently defined in the system:

%lsmagic

Writing latex¶

Let’s use %%latex to render a block of latex:

%%latex

$$F(k) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x) e^{2\pi i k} \mathrm{d} x$$

Running normal Python code: execution and errors¶

Not only can you input normal Python code, you can even paste straight from a Python or IPython shell session:

>>> # Fibonacci series:

... # the sum of two elements defines the next

... a, b = 0, 1

>>> while b < 10:

... print(b)

... a, b = b, a+b

In [1]: for i in range(10):

...: print(i, end=' ')

...:

And when your code produces errors, you can control how they are displayed with the %xmode magic:

%%writefile mod.py

def f(x):

return 1.0/(x-1)

def g(y):

return f(y+1)

Now let’s call the function g with an argument that would produce an error:

import mod

mod.g(0)

%xmode plain

mod.g(0)

%xmode verbose

mod.g(0)

The default %xmode is “context”, which shows additional context but not all local variables. Let’s restore that one for the rest of our session.

%xmode context

Running code in other languages with special %% magics¶

%%perl

@months = ("July", "August", "September");

print $months[0];

%%ruby

name = "world"

puts "Hello #{name.capitalize}!"

Raw Input in the notebook¶

Since 1.0 the IPython notebook web application supports raw_input which for example allow us to invoke the %debug magic in the notebook:

mod.g(0)

%debug

Don’t forget to exit your debugging session. Raw input can of course be used to ask for user input:

enjoy = input('Are you enjoying this tutorial? ')

print('enjoy is:', enjoy)

Plotting in the notebook¶

Notebooks support a variety of fantastic plotting options, including static and interactive graphics. This magic configures matplotlib to render its figures inline:

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

x = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 300)

y = np.sin(x**2)

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.title("A little chirp")

fig = plt.gcf() # let's keep the figure object around for later...

import plotly.figure_factory as ff

from plotly.offline import init_notebook_mode, plot

from IPython.core.display import display, HTML

# Add histogram data

x1 = np.random.randn(200) - 2

x2 = np.random.randn(200)

x3 = np.random.randn(200) + 2

x4 = np.random.randn(200) + 4

# Group data together

hist_data = [x1, x2, x3, x4]

group_labels = ['Group 1', 'Group 2', 'Group 3', 'Group 4']

# Create distplot with custom bin_size

fig = ff.create_distplot(hist_data, group_labels, bin_size=.2)

# plot directly in notebook

#fig.show()

# embed graphic for html, etc. output

init_notebook_mode(connected=True)

plot(fig, filename = 'plotly_test.html')

display(HTML('plotly_test.html'))

The IPython kernel/client model¶

%connect_info

We can connect automatically a Qt Console to the currently running kernel with the %qtconsole magic, or by typing ipython console --existing <kernel-UUID> in any terminal:

%qtconsole

Saving a Notebook¶

Jupyter Notebooks autosave, so you don’t have to worry about losing code too much. At the top of the page you can usually see the current save status:

Last Checkpoint: 2 minutes ago (unsaved changes)

Last Checkpoint: a few seconds ago (autosaved)

If you want to save a notebook on purpose, either click on File > Save and Checkpoint or press Ctrl+S.

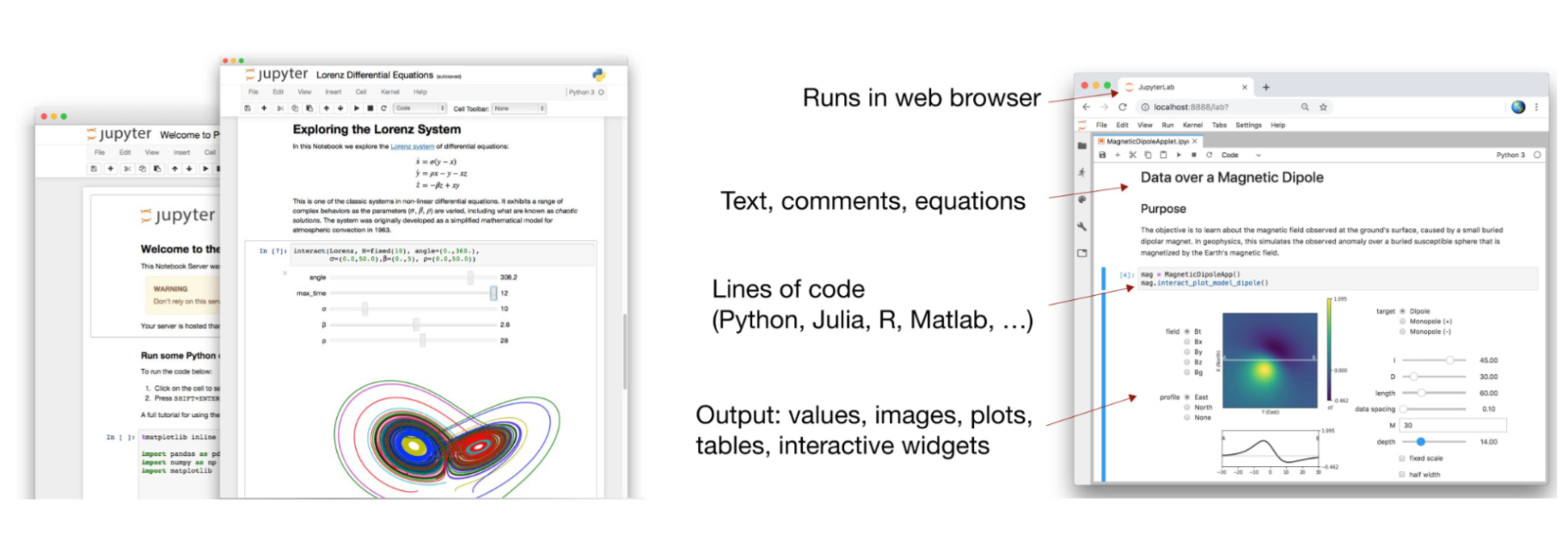

To Jupyter & beyond¶

Open a terminal

Type

jupyter lab

If you’re not automatically directed to a webpage copy the URL printed in the terminal and paste it in your browser

Click “New” in the top-right corner and select “Python 3”

You have a

Jupyter notebookwithinJupyter lab!